|

|

|

Young Suicide Attempters: A Comparison Between a Clinical and an Epidemiological Sample.

(Statistical Data Included) BERIT GROHOLT; OIVIND EKEBERG; LARS WICHSTROM; TOR HALDORSEN.

Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, July 2000 v39 i7 p868

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2000 Lippincott/Williams & Wilkins

ABSTRACT

Objective: To compare risk factors for self-harm in 2 groups: hospitalized adolescents who had attempted suicide and adolescents reporting suicide attempts in a community survey.

Method: All suicide attempters aged 13 to 19 years admitted to medical wards (n = 91) in a region of Norway were assessed and interviewed. Risk factors were identified by comparisons with a general population sample participating in a questionnaire study in the same community (n = 1,736). In this population sample, a separate analysis of risk factors for reporting deliberate self-harm (n = 141) was performed, applying bivariate and multivariate logistic regression models.

Results: Adjusted risk factors for suicide attempts in hospitalized adolescents were depression (odds ratio [OR] = 4.7), disruptive disorders (OR = 9.4), low self-worth (OR = 1.3), infrequent support from parents (OR = 3.3) or peers (OR = 3.3), parents' excessive drinking (OR = 4.3), and low socioeconomic status (OR = 2.4). For adolescents who self-reported self-harm, depression (OR = 3.1) and loneliness (OR = 1.13) were significant adjusted risk factors (p [less than] .001). Low self-worth, low socioeconomic status, and little support from parents or peers characterized hospitalized suicidal adolescents compared with those who were not hospitalized.

Conclusions: The risk factors were more powerful for hospitalized than for nonhospitalized adolescents. Prevention efforts should target the same factors for both groups, at a population level for nonhospitalized adolescents and at an individual level for hospitalized adolescents, with a focus on depression, low self-esteem, and family communication. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2000, 39(7):868-875.

Key Words: adolescents, mental health, self-harm, suicide attempt.

Suicidal behavior is increasingly regarded as a continuum, rather than constituting different types of behavior. In spite of some discontinuities (Gould et al., 1998), this implies that the difference in etiology between completed suicide, attempted suicide, and suicidal ideation is one of degree rather than one of kind (King, 1997). The severity and duration of suicidal thoughts correlate with the likelihood of a suicide attempt (Lewinsohn et al., 1996), and an attempt increases the risk for suicide (Brent, 1995; Groholt et al., 1997). Thus knowledge of risk factors for suicide attempts is important in suicide preventive work and will guide the clinician in the important task of assessing suicidal adolescents.

In the past 20 years, important knowledge about adolescents involved in nonfatal suicidal behavior has emerged from 3 types of studies: studies of suicidal patients in psychiatric treatment, studies of adolescents admitted to emergency wards for medical care, and epidemiological studies. These studies focus on different populations, but it is not well known how the populations differ. The adolescents in the last 2 types of studies, which will be the focus of the present report, differ with regard to the medical seriousness of their attempts. Moreover, the emergency ward group is studied at the time of suicidal behavior, whereas years may have passed since the suicide attempt when epidemiological studies are carried out. The emergency ward groups have been seen by helping professionals, whereas only 6% of those reporting a suicide attempt in a large Norwegian epidemiological study had received treatment in hospital or from a general practitioner for problems relating to their attempt (Rossow and Wichstrom, 1997)

One might speculate that the continuum hypothesis also applies to different suicide attempt samples. More specifically, emergency ward samples and adolescents reporting attempted suicide in population studies may be characterized by the same risk factors, although more pronounced among the hospitalized. Alternatively, the samples may be indistinguishable, differing only with regard to method and closeness in time to the attempt, or there may be systematic differences in other respects as well. Similarities and differences between these 2 samples have important implications for both research and practice. If similar predictors are the prevailing finding, results can cautiously be generalized across samples to build a more coherent picture of suicidal behavior. At present, however, we do not know whether preventive measures based on information from epidemiological studies are effective also for patients treated in medical wards.

To explore similarities and differences between the 2 types of samples, the 2 groups should preferably be compared using the same methods in the same geographical area at the same period. To our knowledge this has not been done, with few exceptions: Both Garrison et al. (1993) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Kann et al., 1995) found that nonwhite adolescents received medical care more often after suicide attempts than did white adolescents.

Although less than ideal, comparisons in which procedures, methods, period, and region differ may also shed light on potential differences and similarities between the 2 samples. Studies based on epidemiological samples of adolescents are numerous, and they provide important knowledge for clinicians (Brent, 1995; Lewinsohn et al., 1996). The prevalence of depression ranges from 31% to 69%, and the increased risk of suicide attempt expressed as an odds ratio was greater than 10 (Andrews and Lewinsohn, 1992; Brent, 1995; Fergusson and Lynskey, 1995). Rates of disruptive disorders range widely, from 17% to 45% (Andrews and Lewinsohn, 1992), with most odds ratios below 10 (Velez and Cohen, 1988). Studies from emergency medical wards are fewer and less uniform (Spirito et al., 1989). The prevalence of depression ranges from 30% to 60% (Rotheram-Borus and Trautman, 1988; Spirito et al., 1989), while 20% to 45% have disruptive disorders (Beautrais et al., 1996; Rotheram-Borus and Trautman, 1988; Spirito et al., 198 9).

The relationship between anxiety and suicide attempt is unclear (King, 1997). In contrast to Gould et al. (1998), some report anxiety disorders to be a risk factor that disappears when one controls for depression (Beautrais et al., 1996; Lewinsohn et al., 1994). Other important risk factors for suicide attempt are family difficulties (Beautrais et al., 1996; Kerfoot et al., 1996; King, 1997; Spirito et al., 1989) and not seeking help when depressed (Culp et al., 1995).

The findings from epidemiological and clinical samples are difficult to compare, as they have been studied at different times and in different geographical areas. Different definitions of what constitutes a suicide attempt also complicate comparisons. The results are probably influenced by the wording of the question asked in epidemiological studies about the suicide attempt and by the definition used in clinical samples. In some studies "an intent to die" is included explicitly, in others not.

In sum, methodological problems faced when comparing hospitalized adolescents who have attempted suicide and adolescents who self-report suicide attempts are numerous, and strong conclusions are therefore precluded. However, no systematic differences between the 2 groups have emerged so far.

In this report we will compare adolescents admitted to the hospital for medical care after deliberate suicide-related self-harm and a representative group of adolescents from a contemporary epidemiological study. Demographic variables, mental health, behavior problems, and parent and peer relationships are examined. We will also study the effect of these variables on deliberate self-harm in the population sample. The aim is to address whether the medical patient population is closer to the completion end of the spectrum of suicidal behavior than those in the community reporting self-harm, by comparing risk factors.

METHOD

Sample 1

The hospitalized attempted suicide sample (HAS) consisted of all youths between 13 and 19 years of age admitted to hospitals for a suicide attempt from June 1993 to December 1994 in an urban catchment area of approximately 900,000 inhabitants. This included all nonaccidental, intentional self-harming acts requiring medical care in a hospital. After a pilot period in 1 hospital, the study included all 6 general hospitals in Oslo and the surrounding counties. Of 114 admissions, 15 were discharged prior to the research contact or did not want to participate. The research is thus based on information about 91 adolescents with 99 admissions (response rate 87%). Information given at the first attempt is used in the comparisons. Mean age was 17.0 years, SD = 1.6; 90% (83/91) were girls. This gave a suicide attempt rate of 351/year per 100,000 girls and 47/year per 100,000 boys, 15 to 19 years old, in Oslo. Nonparticipants did not differ significantly from those taking part in the study with regard to age, sex, or s uicide method.

Sample 2

The comparison group consisted of average adolescents (AA), including a subgroup with self-reported self-harm (SRSH). A survey representative of the population in Norway, with a response rate of 80.1% (n = 8,573), was performed in 1994. All respondents living in the research area who were 13 to 19 years of age, mainly 15 and older (mean age 17.2, SD 1.4; 52% girls), were included as the representative sample of adolescents (AA) (n = 1,736). All adolescents were stratified into groups, by years of age, for both sexes.

To the question, "Have you ever on purpose taken an overdose of medication or tried to harm yourself in other ways?" 141 answered yes (mean age 17.2, SD = 1.4; 77% girls). Three (2%) of these reported that they had been hospitalized, all before the research period. Analyses without these 3 did not change the results reported.

Procedure

After admission to the hospital after a suicide attempt, the first author conducted the psychiatric evaluation. The adolescents were interviewed in the course of 1 week after admission, and most often within 24 hours. The initial open interview was followed by 1 to 5 later interviews, usually conducted in the homes of the adolescents (mean 4.9 hours of contact, SD = 1.4, range 1.5-6.5). Family members were included when possible (71%). Some of the assessment instruments were added after a pilot period comprising 26 attempters and were thus given to 65 (71%) of the 91 attempters. These 26 adolescents did not differ from those in the main study.

Assessment Measures. Diagnoses among the HAS were made according to DSM-IV, Axis I (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) by the first author on the basis of all available information. Another psychiatrist made a diagnosis based on descriptions of the interviews with 30 randomly selected adolescents, with an interrater k of 0.79. In the index group (HAS), affective disorders included major depressive disorder and dysthymia. Anxiety disorders included obsessive-compulsive disorder, simple phobia, social phobia, and agoraphobia. Depressive symptoms were also measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), with a cutoff of 18/19 on the total score, the best discrimination between mild and moderate depression (Becker al., 1988). In the comparison group (AA), depressive symptoms were measured by the Depressive Mood Inventory (DM1) (Kandel and Davies, 1982), with a cutoff point set at 2.99. The DMI is a 6-item measure developed from the Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90) (Derogatis et al., 1974) for use with adol escents. Reliability and construct validity have been shown to be good. These 6 items were added to 10 items from a short version of SCL-25 developed by Hammer and Vaglum (1990). As 4 items were overlapping, a 12-item measure was used, covering symptoms of depression and anxiety. A cutoff for anxiety symptoms was set at 2.75 at the Anxious scale, which gave a prevalence in the expected range in the community sample. All other variables were measured in the same way among HAS and AA. Disruptive behavior disorder was measured using the criteria of Wichstrom et al. (1996) and adapted to DSM-IV criteria. The adolescents were asked whether they had used illegal substances (cannabis and hard drugs) and how often they were intoxicated during the preceding 4 weeks.

Family Constellation and Peer Relationships. Socioeconomic status (SES) was measured according to the International Standard Classification of Occupation (ISCO-88) (International Labour Office, 1990). The occupations of the father (mother) were coded into a 5-point scale: professional leaders (I), intermediate strata (II), clerical workers (III), manual workers (IV), and farmers/fishermen (V). No occupation, leading to public assistance or welfare, was added as group VI. The country of birth of the father (mother) was recorded. Family structure was categorized according to which of the parents the adolescents lived with. Observations of parents being drunk were rated by the adolescents on a 5-point scale, from never to several times each week. A cutoff point was set, and those drunk "sometimes each month" or more (2 highest points on the scale) were categorized as frequently drunk. Feelings of loneliness were measured by a short version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale consisting of 4 items with scores ranging f rom 1 to 4, with 4 indicating maximum loneliness. This is a scale known to have good validity and reliability (Russell et al., 1980). Both samples were asked whether and how they socialized with friends, with 2 or 3 friends or as members of a group. They were also asked whom they turned to in 3 different situations (having trouble with police, feeling very low, or considering future plans for education, respectively), on a scale modeled after Buhrmester (1990) and Meuus (1989). Whether the adolescents turned to parents in any of these situations was recorded on a scale from 0 to 3. Identical scales were recorded for "peers" and for "anybody at all." Self-esteem was measured with a revised version of Hatter's Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (Harter, 1988; Wichstrom, 1995) using the subscale Global Self-Worth, with 5 items with scores ranging from 1 to 4 (4 indicates the best score possible).

Data Analysis

The means of continuous variables were compared with independent sample t test and with the Fisher exact test for categorical variables with the statistical program SPSS. Both the event of HAS, in a population-based case-control design, and SRSH, in a representative cross-sectional design, were analyzed by logistic regression models stratified on sex and age. These well-known designs facilitate comparison with other studies. HAS and SRSH were compared directly by logistic regression models stratified on sex and age. Because of sparse data in some strata, conditional maximum likelihood estimation was used (Breslow and Day, 1980). The computations were made by the statistical program LogXact for Windows (1996). The effects of each variable are presented as odds ratios (ORs) from bivariate analyses and as adjusted ORs from multivariate analyses, including all variables with significant bivariate effect. For the continuous variables the ORs are given for a numeric change of one unit on the total score. Ninety-fi ve percent confidence intervals (CIs) are given. As several comparisons were made, the discussion focuses mainly on differences at a 1% level.

RESULTS

In 4 of the 99 HAS attempts, multiple self-harm methods were used. All the boys and the majority of the HAS girls had taken medication (88%). One girl shot herself, 5 tried to hang themselves, 3 jumped from heights, 6 cut themselves, and 35% had previously attempted suicide. Among the 141 SRSH, only 32% stated their method, which most often was slashing (49%); 31% used medication and 20% used other methods.

Bivariate Comparison With Average Adolescents

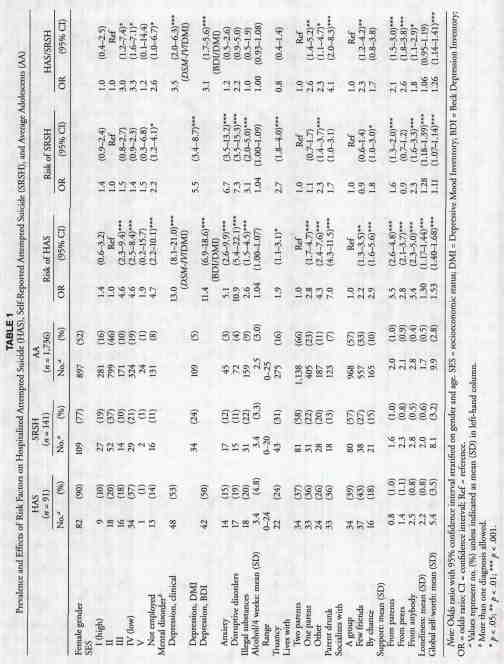

Demographic Variables. Compared with AA, girls comprised a significantly higher percentage among both HAS (p = .000) and SRSH (p = .000). The socioeconomic group of HAS differed significantly from AA ([[chi].sup.2] = 40.7, df = 5, p = .000), unlike SRSH ([[chi].sup.2] = 6.8, df = 5, p = .23). Pairwise analyses showed that HAS more often had unemployed parents or parents belonging to SES III or IV, while SRSH had unemployed parents more often than AA (Table 1). Parents came from a non-Western society; most often from Asia, in 14% of HAS, 7% of SRSH, and 6% of AA, significantly more often in HAS than AA (OR 2.5, CI = 1.2-5.0, p = .019). With control for SES, the effect of this variable disappeared.

Mental Health. Table 1 shows clinical diagnoses among HAS (depression, 53%; anxiety disorders, 15%; and disruptive disorders, 19%) according to DSM-IV, as well as depression based on BDI (scores 19 or more). The mean BDI score for HAS was 18.7 (SD = 11.7, range 0-49). All mental problems (depression, disruption, and anxiety), unadjusted, increased the risk for both types of self-harm. The correlation between BDI and clinical depression among HAS was moderate (Pearson r = 0.57). Several had more mental problems in combination (HAS, 24%; SRSH, 22%), mainly affective problems combined with anxiety (HAS, 8%; SRSH, 8%; AA, 3%) or with substance use (HAS, 6%; SRSH, 7%; AA, 1%) or disruptive disorder combined with substance use (HAS, 10%; SRSH, 5%; AA, 3%). Anxiety was no longer a risk factor after we controlled for depression, regardless of the instrument used.

Behavior Problems and Relationship to Parents and Peers. Compared with AA, both HAS and SRSH had significantly increased levels of a majority of behavior and relational problems (truancy, using illegal substances, seeking little support from parents, feeling lonely) (Table 1). Both suicidal groups had significantly lower global self-esteem than AA, and they more often chose not to seek support from anybody. HAS also seldom received support from peers. Not all factors differentiated adolescents who had harmed themselves from AA. Neither HAS nor SRSH reported using alcohol more frequently than AA. SRSH lived with one parent, used peers for support, and belonged to a peer group as often as AA.

Risk Differences Between HAS and SRSH

There were more females among the HAS group compared with SRSH (OR = 2.7, CI = l.2-5.9,p = .01). The following unadjusted factors were also significantly more prevalent among the HAS than the SRSH group: low SES (Table 1), living without 2 parents, parents frequently drunk, not seeking support, seeing few friends without belonging to a group of peers, global self-worth, and also depression, which was estimated with different measurements, however. No significant differences were found between HAS and SRSH regarding anxiety, disruptive disorders, frequent drinking, and loneliness. The average number of examined risk factors for each adolescent was significantly higher for both HAS (3.5, SD = 1.7) and SRSH (2.1, SD = 1.6) compared with AA (1.3, SD = 1.2) and for HAS compared with SRSH (p = .000).

Multivariate Analyses

All variables significant in simple logistic regression were included in a multiple logistic regression, stratified on age and gender (Table 2). The following factors independently increased the risk of HAS (p [less than] .01): depressive disorder (OR = 4.7), disruptive disorders (OR = 9.4), parents being seen drunk more than twice each month (OR = 4.3), seldom seeking parents (OR = 3.3) or peers (OR = 3.3) for support, and low global self-esteem (OR = 1.3). In addition, SES lower than II or receiving welfare (OR = 2.4) and living without 2 parents (OR = 2.4) increased the risk of HAS. The risk of SRSH was increased by depression (OR = 3.1) and also (p [less than] .05) truancy, low self-esteem, and feeling lonely (OR = 1.13). With multiple logistic regression, a direct comparison between HAS and SRSH showed that HAS sought support significantly (p [less than] .001) less often from parents and peers, and they had lower (p [less than] .05) self-esteem and SES. As a consequence of measurement differences for de pression, the multivariate analyses were done without including depression, and the independent effect of the variables in Table 2 remained the same with one minor exception: Disruptive disorders increased the risk for SRSH (OR = 2.7, CI = 1.0-7.0, p = .04).

DISCUSSION

Several factors increased the risk for both hospitalized

and SRSH adolescents, underlining the multifactorial nature of

suicidal behavior. Depressive and disruptive disorders, disadvantaged

families, little support from parents and peers, and low self-esteem

independently increased the risk for HAS (p [less than] .01),

while depression had the strongest independent effect on SRSH.

Compared with the self-harming adolescents in the epidemiological

sample, the hospitalized adolescents were more burdened, as all

factors except illegal substances exerted a stronger independent

effect on HAS, even if only little support, low self-esteem, and

low SES showed significant independent differences between HAS

and SRSH. Unlike the hospitalized adolescents, the nonhospitalized

self-harming adolescents resembled AA in their relationship with

peers. They saw themselves as belonging to peer groups and sought

support from peers, as did the AA. The SRSH also had better self-esteem

than the hospitalized group even if they, like the hospitalized

group, were affected by depression and feelings of loneliness.

Demographics

It is well known that more females than males attempt suicide (King, 1997), as found in this study. Overdose of medication, most often used by girls (Moscicki, 1994), dominated among those admitted to the hospital and may contribute to the significant sex difference between HAS and SRSH. The increased risk for suicide attempt associated with low social class is more pronounced for the hospitalized adolescents and is in line with previous findings (King, 1997). The higher prevalence of non-Western parents among the hospitalized attempters was explained by their significantly lower SES.

Affective and Behavior Problems

Depression, disruptive disorders, and anxiety were common among both groups with suicidal behavior, as found in previous studies of the same age group (Brent, 1995). In spite of methodological problems in reliably estimating increased risks for hospitalized adolescents, all findings support the notion that depression independently increased the risk of both suicidal groups. The prevalence of disruptive disorders in the community is lower in Norway than in the United Stares (Groholt et al., 1997), but when unadjusted, these disorders were highly correlated with self-harm in both hospitalized and nonhospitalized adolescents. The effect remained strong for the hospitalized adolescents when controlled for all other risk factors, including truancy and substance use, while the adjusted effect on the nonhospitalized suicidal adolescents was statistically non-significantly increased. However, there was no significant difference in the rates of disruptive disorders between the suicidal groups, unadjusted or adjusted.

As found by Gould et al. (1998), anxiety increased the risk for self-harm, but not when controlled for depression, as found by Beautrais et al. (1996) and Lewinsohn et al. (1994), probably because depression itself explains all the variance when it coexists with anxiety. Gould found a higher prevalence of anxiety using clinical diagnoses (controls 18%) than we found with the anxiety scale (3%). Different measures may explain the discrepancy.

Thus, mental disorders did not differentiate significantly between the suicidal groups in adjusted analysis, even if the prevalence rates were highest among the hospitalized group. However, low self-esteem, which had an independent effect on both suicidal groups, also differentiated between the groups and may be a mediating factor in making suicidal behavior progress toward more serious forms, as found by Lewinsohn et al. (1996). Another possible interpretation is that the low self-esteem among the hospitalized adolescents is related to the closeness in time to a crisis precipitating the suicidal behavior, but this question cannot be answered in the present study.

Relationship to Others

In line with the findings of Gould et al. (1996), this study underlines the importance of having a confiding relationship with parents, as this protected against all types of self-harm, and differentiates between the suicidal groups. Generally, the hospitalized group had a relationship pattern that deviated from the pattern of the AA. They seldom belonged to a group of peers, but more often socialized with one or two friends. They seldom sought support among their friends or their parents, but when they did, this had a protective function. The relationship problems of the SRSH were generally less prominent. They used their parents for support more often than HAS, and their relationship to peers resembled that of the AA. However, they often felt lonely even if they belonged to peer groups and sought support from peers as often as the AA group. Peer support did not protect against self-harm, whereas support from parents did.

Strengths and Limitations

.gif)

The completeness of the hospitalized

sample and the large sample size of the community adolescents

in this study are positive assets. The assessment of a fairly

large number of variables provided an opportunity to explore how

these variables increased suicide attempt risk alone and in combination.

The samples are representative of one region contemporaneously,

with uniform availability of care, which makes comparison between

hospitalized and community samples possible. This distinguishes

the study from previous research. Both groups are studied in well-known

designs: the event of HAS, in a population-based case-control

design, and SRSH, in a representative cross-sectional design.

On the other hand, the difference between the samples gives rise to methodological problems. The comparability between the different measures of depression used in this study is an important issue. Clinical diagnoses of depression differ from depressive mood as determined by cutoff points in self-rating instruments (Fechner-Bates et al., 1994). The Pearson correlation (r) between the DMI and a clinical diagnosis of major depressive disorder in adolescents was found by Kandel and Davies (1982) to be 0.43. The correlation between the BDI and the SCL-90, from which the DMI is constructed, was good, and it varied from 0.66 to 0.83 (Beck et al., 1988; Margo et al., 1992; Moffett and Radenhausen, 1990). In our study the estimated risk (OR) for HAS was the same whether we compared the DMI with the BDI diagnosis or with a clinical DSM-IV diagnosis. Our conclusion is thus that depression increases the risk for both HAS and SRSH. However, as different instruments were used, a comparison of risks between the samples is not warranted.

Even though other variables were measured with the same self-report forms in all samples, the different settings and amount of time since the self-harm may be influential. The hospitalized adolescents, in contrast to the SRSH adolescents, had personal contact with the researcher immediately after the self-harm, and the acuteness of a suicidal crisis may increase the number of problems reported, thus exaggerating the differences between the samples.

Conclusions

Within the context of suicidal self-harm, not including suicidal ideation, hospitalization and self-report of deliberate self-harm seem to represent different points on a continuum of suicidal behavior. The unadjusted risk factors were mainly the same. Both suicidal groups had mental and behavior problems and received little parent support. However, the hospitalized adolescents had more problems, were more frequently depressed, had more dysfunctional families, had lower self-esteem, and unlike self-reporters did not feel integrated in peer groups. In the adjusted analysis all risk factors except illegal substance use were larger for HAS, but only social support from peer and parents, low self-esteem, and SES showed a significant difference, underlining the importance of relationships, above all to the parents, in the development of suicidal behavior. However, as the relationship to suicidal ideation has not been addressed, a continuum hypothesis has not been explored fully.

In sum, both groups had several problems. Low self-esteem and lack of support from parents and from peers may act as mediators and cause suicidal behavior to progress to more serious forms. This is in line with a model described by Lewinsohn et al. (1996), and the same risk factors are found among suicide completers (Brent, 1995).

Clinical Implications

The existing literature on preventive measures stresses interventions that are appropriate to reduce the risk factors found in this study. Preventive efforts toward adolescents reporting self-harm can reasonably be given at a population level. This large group of adolescents may be influenced by general attitudes, as they see themselves as part of peer groups. Professionals meeting adolescents need to be aware of unrevealed suicidal ideas; this includes disruptive adolescents, who may have rapidly fluctuating suicidal impulses.

Preventive measures directed toward a first attempt can reasonably be regarded as the same as those directed toward prevention of further attempts, even if the latter is more likely to be associated with risk factors. Thus, on an emergency ward, the clinical efforts should be directed toward the same risk factors, on an individual level. Help should be directed toward families, to increase intrafamilial communication and reduce other disadvantages. Many problems faced by hospitalized adolescents are serious, however, and do not respond easily to treatment. The very low self-esteem among the adolescents warrants a follow-up after the acute crisis intervention. Low self-esteem may be related to disadvantaged family background and to lack of positive integration in peer groups. Clinically, the lack of integration may prevent a better feeling of self-worth, and a vicious circle may occur. Thus help should be directed toward the adolescents on an individual level to enforce already existing coping skills, using, for instance, social skills training and cognitive therapy.

The prevalence of depression found in this study is high, and measures to increase recognition and treatment of depression should be incorporated in prevention both at an individual and at a population level.

Dr. Groholt is Research Fellow, Department Group of Psychiatry; Dr. Ekeberg is Professor, Department of Behavioral Sciences in Medicine; and Mr. Haldorsen is Senior Statistician, Department of Medical Statistics, University of Oslo, Norway.

Dr. Wichstrom is Professor, Department of Psychology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway.

This study was funded by the Research Council of Norway. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Professor Emerita Hilchen Sommerschild, M.D., Professor Philip Graham, F.R.C. Psych., and Professor Bjorn Rishovd Rund, Ph.D., University of Oslo.

Reprint requests to Dr. Groholt, Center for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, P.O. Box 26, Vinderen, N-0319 Oslo, Norway; e-mail: groholt@online.no.

0890-8567/3907-0868@2000 by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

REFERENCES

American Psychiatric Association (1994), Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association

Andrews JA, Lewinsohn PM (1992), Suicidal attempts among older adolescents: prevalence and co-occurrence with psychiatric disorders. J Am Acad Chi Child Adolesc Psychiatry 31:655-662

Beautrais AL, Joyce PR, Mulder RT (1996), Risk factors for serious suicide attempts among youths aged 13 through 24 years. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35:1174-1182

Beck AT, Steer RA, Garbin MG (1988), Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 8:77-100

Brent DA (1995), Risk factors for adolescent suicide and suicidal behavior: mental and substance abuse disorders, family environmental factors, and life stress. Suicide Life Threat Behav 25(suppl):52-63

Breslow NE, Day NE (1980), Statistical Methods in Cancer Research, Volume 1: The Analysis of Case-Control Studies. Lyon, France: IARC Scientific Publications

Buhrmester D (1990), Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Dev 61:1101-1111

Culp AM, Clyman MM, Culp RE (1995), Adolescent depressed mood, reports of suicide attempts, and asking for help. Adolescence 30:827-837

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L (1974), The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci 19:1-15

Fechner-Bates S, Coyne JC, Schwenk TL (1994), The relationship of self-reported distress to depressive disorders and other psychopathology. J Consult Clin Psychol 62:550-559

Fergusson DM, Lynskey MT (1995), Childhood circumstances, adolescent adjustment, and suicide attempts in a New Zealand birth cohort. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 34:612-622

Garrison CZ, McKeown RE, Valois RF, Vincent ML (1993), Aggression, substance use, and suicidal behaviors in high school students. Am J Public Health 83:179-184

Gould MS, Fisher P. Parides M, Flory M, Shaffer D (1996), Psychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53:1155-1162

Gould MS, King R, Greenwald S et al. (1998), Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 37:915-923

Groholt B, Ekeberg O, Wichstrom L, Haldorsen T (1997), Youth suicide in Norway, 1990-1992: a comparison between children and adolescents completing suicide and age- and gender-matched controls. Suicide Life Threat Behav 27:250-263

Hammer T, Vaglum P (1990), Initiation, continuation or discontinuation of cannabis use in the general population. Br J Addict 85:899-909

Hatter S (1988), Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents. Boulder: University of Denver

International Labour Office (1990), ISCO-88 International Standard Classification of Occupation. Geneva: Corporate Authors ILO

Kandel DB, Davies M (1982), Epidemiology of depressed mood in adolescents: an empirical study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 39:1205-1212

Kann L, Warren CW, Harris WA et al. (1995), Youth risk behavior surveillance--United Stares, 1997. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ 44:1-56

Kerfoot M, Dyer E, Harrington V, Woodham A, Harrington R (1996), Correlates and short-term course of self-poisoning in adolescents. Br J Psychiatry 168:38-42

King CA (1997), Suicidal behavior in adolescence. In: Review of Suicidology, Maris RW, Silverman MM, Canetto SS, eds. New York: Guilford, pp 61-95

Lewinsohn PM, Roberts RE, Seeley JR, Rohde P, Gotlib IH, Hops H (1994), Adolescent psychopathology, II: psychosocial risk factors for depression. J Abnorm Child Psychol 103:302-315

Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR (1996), Adolescent suicidal ideation and attempts: prevalence, risk factors, and clinical implications. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 3:25-46

Margo GM, Dewan MJ, Fisher S, Greenberg RP (1992), Comparison of three depression rating scales. Percept Mot Skills 75:144-146

Mcuus W (1989), Parental and peer support in adolescence. In: The Social World of Adolescents; International Perspectives, Hurrelmann K, Engel U, eds. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, pp 167-183

Moffett LA, Radenhausen RA (1990), Assessing depression in substance abusers: Beck Depression Inventory and SCL-90R. Addict Behav 15:179-181

Moscicki E (1994), Gender differences in completed and attempted suicides. Ann Epidemiol 4:152-158

Rossow I, Wichstrom L (1997), When need is greatest: is help nearest? Help and treatment after attempted suicide among adolescents (in Norwegian). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 117:1740-1743

Rotheram-Borus MJ, Traurman PD (1988), Hopelessness, depression, and suicidal intent among adolescent suicide attempters. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27:700-704

Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE (1980), The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol 39:472-480

Spirito A, Brown L, Overholser J, Fritz G (1989), Attempted suicide in adolescence: a review and critique of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev 9:335-363

Velez CN, Cohen P (1988), Suicidal behavior and ideation in a community sample of children: maternal and youth reports. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 27:349-356

Wichstrom L (1995), Harter's Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents: reliability, validity, and evaluation of the question format. J Pers Assess 65:100-116

Wichstrom L, Skogen K, Oia T (1996), Increased rate of conduct problems in urban areas: what is the mechanism? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 35:471-479